Not all Legs are Created Equal

It is not uncommon for people to have one leg shorter/longer than the other. In fact, statistically up to 35% of people have a difference of 0.5 to 1.5 cm (0.2 to 0.6 inches). This variance in leg length almost always requires no treatment or intervention.

There are many causes, besides having had polio, that can affect one leg more than the other particularly in a growing child. These include some genetic conditions; a fracture, injury, or tumor of the femur or tibia that affected the epiphyses (growth plate at the ends of the bone); a fracture that healed in a shortened position; abnormal growth of tissues on one side of the body (hemihyperplasia); or other neuromuscular problems such as cerebral palsy that affect alignment around joints in the leg, pelvis, or back.

In the case of muscle weakness in one leg, it can be useful to have the weaker leg be a little shorter because it can be swung forward to take the next step using pendulum activity and not require lifting the limb as high to clear the toes which decreases the energy required to take a forward step.

A shortened limb often happened when polio occurred in a growing child - generally the bones in girls grow until around age 14 and in boys until around age 16. Wolff’s law states “bones adapt to the amount of mechanical stress they experience”. If a limb is weak and is used less to exert pressure to lift things or bear weight or if there is not the normal pull of muscle on a bone in that extremity, the bone will not grow at the same rate as a bone that experiences normal mechanical stresses. This may be expressed by one foot being smaller than the other, one leg being shorter than the unaffected leg, or one hand/arm being smaller than the other. When a leg is shorter, the person needs to make accommodations like that made by a person who steps into a hole with one foot while they are walking. The back may also bend toward the shortened side as weight is applied to the shorter leg.

Scoliosis (S-shaped curvature of the spine side to side) can also make one leg appear shorter than the other as the hip is “pulled up” on the shorter side of the curve. Or sometimes malalignment of the sacro-iliac (SI) joint in the pelvis can cause a “functional” leg length difference. Functional means that the person’s leg length appears to be different but the actual length of the bones in that limb are equal to the other side.

How is a leg length difference determined? It can be determined and measured in several ways. The most accurate is taking x-rays of the lower and upper leg bones and measuring the length of the femur (thigh bone) and the tibia (the bigger bone in the lower leg). However, this exposes the person to radiation and this degree of accuracy is rarely needed.

Most commonly leg length measurement is estimated by the clinician having the person stand barefoot with their back to the examiner and the examiner places his/her hands on the iliac crests (the bones at each side of the top of the pelvis that one places their hands on when standing to express disgust or impatience).

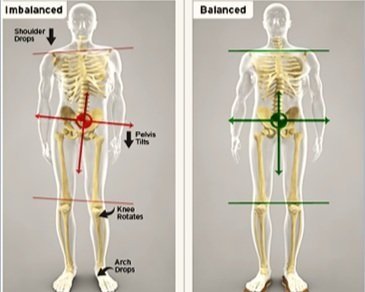

The examiner then visually assesses whether both of their hands are level with each other or if one hand is higher than the other. The higher hand indicates that leg is actually or functionally longer than the other. A similar process can be used to determine the amount of leg length difference by placing objects with a known thickness under the shorter leg until the pelvis is leveled.

A measurement can also be made using a tape measure and measuring the leg lengths when a person is supine (lying on their back). The measurement can be made from a bony prominence at the top of the pelvic bone (anterior superior iliac spine) down to the tip of the medial malleolus (the ankle bone on the inside of the leg) or from the umbilicus (belly button) down to the medial malleolus of the leg to be measured. These measurements may be misleading if the person has a scoliosis affecting the lumbar spine or a SI joint dysfunction.

What kind of problems can a leg length discrepancy (LLD) cause? It can cause back pain as abnormal forces are now transmitted to the low back. It can cause a limp as the person compensates by leaning toward the side with the shorter leg when stepping onto that leg.

What can be done about a LLD? The simplest treatment is to add length to the shorter leg by placing a lift inside or outside the shoe on the shorter leg. Up to about ½ inch heel lift can be placed inside the shoe; more than ½ inch will cause the person’s heel to come above the heel cup of the shoe and the shoe may not enclose the person’s heel sufficiently to feel secure. Lifts can also be added to the sole of most, but not all, shoes. This can be done by an orthotist or a shoe repair person. If the leg length is significant and longstanding without any treatment, the body may have adapted to the mis-alignment with minimal symptoms. Totally correcting the LLD, especially if it is more than 1-1.5 inches, all at once may cause new or increased back pain or unstable gait. However, if the difference is corrected in increments, such as ¼ to ½ inch at a time, the body will more easily adapt to the new alignment. External lifts will add weight to the shoe, are moderately expensive, and may not be covered by one’s health insurance.

Many polio survivors with a LLD had a surgery called epiphysiodesis done before their growth plates closed. This was done by placing staples across the growth plate or scraping or otherwise damaging the growth plate. This often was successful in decreasing or eliminating the LLD. If the growth rate was not correctly assessed or monitored, at times the “shorter leg” may have now become the longer leg. In this case, a lift might need to be added to the shoe on their polio- unaffected leg.

Other surgical procedures used to treat LLD include removal of a section of bone from the longer femur and allowing it to heal in a shortened state or a bone lengthening procedure done on the femur of the shorter leg in which a cut is made across the femur into two segments and slowly pulling them apart to allow new bone to form across the gap. (Sometimes called an Ilizarov procedure after the Russian surgeon who developed the procedure in the 1950s).

For most polio survivors in their 70s and above, a LLD does not need to be treated unless it is causing back or hip pain, is new (for example, caused by a recent fracture or a hip/knee surgery that caused shortening), or is causing an unstable gait.