Dr. Julius Youngner: Unsung Hero of Polio Eradication

“The Fifth Avenue lab where he and the original five-person team worked was located below a ward of polio patients who couldn’t breathe on their own. Machines, ‘iron lungs’ did it for them, said Youngner. ‘They had these machines that drove the in and out of breathing,’ he said. ‘I mean it just kept them alive.’

The ward was enormously loud. The machines created a terrible din and drove home the reality of the disease, Youngner said. ‘We had motivation right there in the building,’ he said. ‘Everybody was very serious about what we were doing. I never worked so hard in my life. I worked seven days a week’.”

Julius Youngner was born in 1920 in Manhattan, New York, where his father was a businessman. As a child, he was sick quite often and when he was seven, Youngner was nearly killed by lobar pneumonia. All of this left him with a lifelong interest in infectious disease. (1)(2)

Youngner graduated Evander Childs High School, when he was 15 years old, and received a B.A. in English from New York University in 1939. After completing a Sc.D. (Doctor of Science) degree in microbiology at the University of Michigan where he stayed on as a faculty member.

He was drafted into basic U.S. Army infantry training. Upon completion he screened and assigned to a top secret project. The Army assigned him to a top-secret unit in Oak Ridge, Tenn., to examine the toxicity of uranium salts through classified research at University of Rochester School of Medicine. The effects of inhaled uranium salts on human tissue was important to the war effort, as it related to purification of uranium for nuclear research and weapons. Youngner never knew the research was related to weapons until the end of the war. (He thought nuclear energy would be used for planes or submarines for transportation). He had no idea he was working on what would be known as “The Manhattan Project” (the government’s clandestine program to develop an atomic bomb). (1)(2)(3)

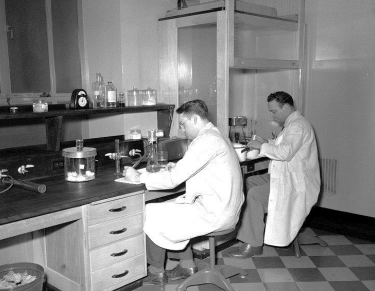

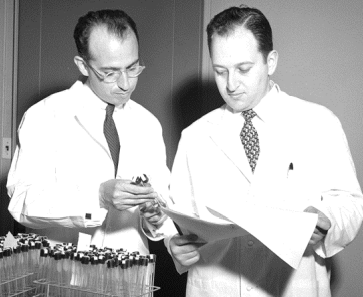

A commissioned officer in the Public Health Service at the Cancer Institute (National Institutes of Health), Julius Youngner discovered his interest in virus research. When he moved to Pittsburgh in 1949, he thought he’d be in the city for two years. He wanted to work on viruses and took a position in a University of Pittsburgh lab directed by Dr. Jonas E. Salk, developing a vaccine for polio.

“The Fifth Avenue lab where he and the original five-person team worked was located below a ward of polio patients who couldn’t breathe on their own. Machines, ‘iron lungs’ did it for them, said Youngner. ‘They had these machines that drove the in and out of breathing,’ he said. ‘I mean it just kept them alive.’

The ward was enormously loud. The machines created a terrible din and drove home the reality of the disease, Youngner said. ‘We had motivation right there in the building,’ he said. ‘Everybody was very serious about what we were doing. I never worked so hard in my life. I worked seven days a week’.” (4)

His contributions to Salk’s vaccine were critical to its success. (3) The most prominent was a rapid color test he designed to measure the amount of poliovirus in living tissue culture. He also developed techniques for trypsinization - a method that used the enzyme trypsin to harvest the polio virus in large quantities. This technique enabled vaccine-makers to produce material to make vaccines for everyone.(3)

The Salk vaccine is based upon formalin inactivated wild type virus. The key to effective inactivation depended upon a color test developed by Youngner, which allowed formalin induced viral protein degradation to be accurately plotted. From Youngner's work, formalin application for six days was projected to produce only "one live virus particle in 100 million doses of vaccine."(1)

By 1954, the first virus trials had immunized 800,000 children against polio.

After his work on the polio vaccine, Youngner made major advancements in the fields of virology and immunology. Together with Pitt colleagues, he explored the antiviral activities of the immune protein interferon and identified what is now known as interferon gamma. Interferon is now used in many cancer therapies. He was an American Distinguished Service Professor in the School of Medicine and Department of Microbiology & Molecular Genetics at University of Pittsburgh. (1)

He received numerous honors and awards, including the Polio Plus Achievement Award from Rotary International in 2001.

He earned an honorary doctor of public service from Pitt in 2005, the Chancellors Medal in 2014, and the department of microbiology and molecular genetics established an annual lecture series in his honor in 2015. (3)

Dr. Julius Youngner died in 2017 at the age of 96.

Words Of Wisdom and Experience from Personal Interviews with Dr. Julius Youngner.

Q: What did you think of the work of Albert B. Sabin, MD, that led to the development of the oral vaccine?

A: Without Dr. Sabin's vaccine, polio would have never been eradicated because of the expense of the [Salk] vaccine and the fact that you needed needle and syringe. Multiple injections with needle and syringe made it not practical for global eradication. Dropping drops in babies' mouths was the way to go, and Dr. Sabin did it. (5)

Q: How does it feel to have played such a significant role in eradicating this disease in the United States?

A: Exhilarating -- and that doesn't even describe it, because I've been on a high ever since. (5)

Q: Before the emergence of HIV, there was a point where it was thought that all infectious diseases had been defeated. Do you think we'll ever be able to actually defeat infectious disease entirely?

A: I really don't think so. Nature is the worst bioterrorist. There will always be new threats. Look at how AIDS appeared in the '80s. SARS came out of nowhere. In 2004, it disappeared, for the time being. Avian influenza in Asia is knocking on our doors. This could be the next pandemic, and nature knows how to do it. (5)

Q: Can you tell me a little bit about the experience of doing research as a part of the polio team?

A: “Well, it was very exciting. Especially since we knew very early on that we were probably going to be successful, because it was successful in monkeys — the vaccine immunized the monkeys, so they didn’t get polio when we challenged them.” (6)

Q: How did you first get involved in Polio research?

A: “I was a commissioned officer at the Cancer Institute in Bethesda, [Maryland], and I wanted to work with viruses and cell culture, but there was no lab space for me to do that. So, they said go anywhere you want, that way you can do what you want, and then come back and you will have a lab. Jonas Salk and I had a joint acquaintance in Ann Arbor, [Michigan], and when he found out I was looking for a position, he called me and said that you can work on cell culture and viruses, but I would like you to first work on polio. And I said, that’s no problem. And the rest is history. So, when it came time for me to go back and work on cell culture and viruses, I stayed on the reserves and worked in Pittsburgh because I knew we were on the way to getting a major vaccine against a major disease. And here I still am.” (6)

Q: How long was the time from the onset of the polio project until the results were able to be published?

A: “We had immunized monkeys by 1951 and then we went to volunteer school children. Then in 1954, they started the big field trial with around 800,000 children in 12 states — that’s a kind of field trial that will never be seen again. It was done double-blind. On April 12, 1955, there was a big announcement made in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where the trial headquarters were and they made the big announcement that the vaccine was successful and it just went around the world like lightning because people were so afraid of polio and the incidence was increasing, especially in upper age groups.” (6)

Q: How would the trial have been different if it had been conducted today (2016) ?

A: “Today, it would have taken us 12 years to do what we did in four and a half years because of all the regulations now - there’s the institutional review board, the FDA, the animal care organization, the federal government. We didn’t even work with laminar flow hoods for safety, and we did mouth-pipetting, which you can’t do anymore. So, it would have taken us much longer if we were starting out now. “It would have been safer for us, and it would have had approval from many different groups before we could go ahead with each stage. We didn’t have to wait for formal approval by Institutional Review Boards for protocols and what we were going to do … And, with the animal care regulations now, our cages for the monkeys would have never passed muster … But, that’s why we did it so fast. That is an amazing thing for the world to recognize — this was done in very short time.” (6)

Q: In the early 1900s, polio was a major epidemic, especially in New York, where 6,000 people died — many of them children — and 21,000 were left temporarily or permanently paralyzed by the epidemic, according to the New York Times. Do you think fear made finding volunteers an easy task?

A: “Absolutely. And not only that, in 1952, when we started doing the human trials in Pittsburgh, this was the height of polio incidence — there were 52,000 cases of paralytic polio in the United States. We also had an incentive because in the building we working in, on the third floor, there were all people in iron lungs and to go up there and see these people in the iron lungs, which were artificial breathing devices, gave us an incentive to work hard. (6)

Q: In regard to grants, how is the process different now than it was 50 years ago?

A: “Well, in those days, the [National Institutes of Health] was not funded the way it is now. The whole development of the polio vaccine was done with only private money provided by what was then called the National Institute for Infantile Paralysis, which is now the March of Dimes, so there was not one penny of federal money. Actually, it gave an incentive and showed the government what can be done when you can spend money on research.”

Q: In your mind, what is the next up-and-coming research discovery?

A: “They are working on the Zika virus and that’s taking a lot of people’s energy. But, when they conquer Zika virus and have a vaccine, there will be something else because nature knows how to fill niches — there is always something new nature can do her tricks with. We never had ebola before, we never had Zika before … so, there is always going to be something new to threaten us and make research essential to solve the problem.” (6)

Q: Will we ever be able to predict what will threaten us next?

A: “No, I don’t think so … you can’t predict where it’s going to come from. Who would have predicted Zika virus? They didn’t even know the name, but it was circulating in Africa somewhere, from some animal and into humans. Then, it broke into populations that had never experienced it before in the Western Hemisphere and Asia, and it spread very easily.” (6)

Q: How has the focus of research evolved over time?

A: “I don’t think the focus has changed because in infectious diseases there are lots of problems that have to be solved. For instance, antibiotic resistance - that’s a problem that is really hard to solve … it is staying ahead of scientific technology. And now, a new disease like Zika, comes into the developed world and is carried by mosquitos, which we have plenty of in this country, and they found out a lot of things about Zika that they never knew - it can be transmitted sexually, by saliva. I mean, it’s really a very unique disease.” (6)

Sources: (1) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julius_Youngner (2) This Week in Virology:373 www.papolionetwork.org/polio-history-videos (3) https://archive.triblive.com/local/pittsburgh-allegheny/julius-youngner-pitt-polio-pioneer-dies-at-96/ (4) https://www.wesa.fm/post/how-pittsburgh-made-polio-vaccine-helped-beat-disease-terrified-nation#stream/0 (5) https://amednews.com/article/20050411/health/304119969/4/ (6) https://pittnews.com/article/111964/top-stories/julius-youngner-polio-vaccine-research-team/