My Toughest Battle: A Soldier’s Lifelong Struggle With Polio

By Bill Matz with Carol Ferguson

I was stricken with polio in August of 1944 during what would be one of the worst epidemics of polio in Philadelphia. My Dad was overseas in the Navy and my mother had taken me to visit with my grandmother in that city.

I was not yet six years old. I tried to get off the living room couch and walk across the room to see her; but I just collapsed on the floor as my leg suddenly gave out. I tried to get up and it gave out again and again. I could not stand up. They called an ambulance, and I was taken to the Philadelphia General Hospital. The spinal tap diagnosed my condition as poliomyelitis, and I was admitted to the hospital right away.

Even though I wasn't quite six years old, there are certain vivid memories we have about incidents in our lives that remain with us forever. I remember being wrapped in a white sheet and that my mother was not allowed to accompany me to the hospital. I realize now that most of us who were stricken with polio in the 1940’s and ‘50’s were all quarantined. Hospitals were afraid to let anybody come in contact with a polio patient for fear of contacting the disease. They braced my right leg immediately. I went from one hospital to the next, until they finally sent me to the Home of the Merciful Savior, on Baltimore Avenue in Philadelphia. My right leg was paralyzed from hip to toe. It was there that the doctor said to my mother “he will never walk again without a brace or crutch.” She was devastated. I was in and out of that hospital until I was officially released from all inpatient/outpatient treatment in 1953. During that nine-year period of rehabilitation, I was being treated by both Dr. Chance and Dr. Cleland.

The Roosevelt administration brought the Australian nurse, Sister Elizabeth Kenny, to the United States to assist in treating polio. Her method differed from the conventional one of placing paralyzed limbs in rigid steel braces or casts. Instead, she applied hot compresses followed by passive movement therapy to the affected area. She eventually visited the Home of the Merciful Savior. One out of every five kids was chosen to have her treatment. I was very, very lucky to be one of those selected for the Kenny treatment. According to my records, I started those sessions after she trained some of the staff. I remember that the treatments were three times a day. Each hour-long session consisted of removing my brace, wrapping my leg in hot packs made of wool, followed by gentle massage and limb therapy. After I rested awhile, they repeated the process. I can still remember the steam and smell coming from those red-hot woolen hot packs. I had that treatment for several months. Finally, they said “no more braces for Bill Matz!” To this day, I am thankful for the amazing support of my parents and for those Sister Kenny treatments.

When I was an inpatient, the hospital staff held contests where they would line up the kids who had paralytic polio in their legs, to see how far you could walk without the aid of a brace or a crutch. They actually let you fall on the lightly padded floor, so that you didn't hurt yourself, and then they marked an X on the spot on the floor where you fell. That's how far you went that day. Looking back, I think that's where I started to develop my competitiveness. I didn't want to lose. I didn't want anybody to beat me, especially a girl. I was only six, seven years old then, but those contests instilled in me that grit and fighting competitive spirit that I needed. Again, I just didn't want anybody to beat me, and very few ever did! I certainly did not want to be a cripple for life.

The wing next to me was the Bulbar polio wing, which had all the iron lung patients. I remember when they pushed me by that wing in a wheelchair and looking briefly through the door where I saw two rows of about 20 beds each. All you could see were the small heads jutting out from the end of the iron lungs, and you heard that sound - “swoosh” . . “swoosh.” As a young child, this was very upsetting. I still see those iron lungs. It is a memory permanently and indelibly etched in my mind forever. I felt so sorry for those kids and knew I never wanted to experience anything like that. I had wonderful treatment at the Home of the Merciful Savior. I was eventually released as an outpatient while still requiring a brace and crutch. I remain in touch with the Home’s staff today and support their programs where I can.

World War II ended and my dad came home from the Navy and was discharged on Christmas Eve 1945. A few years later, he was able to buy a small twin house in East Lansdowne, PA., using the GI Bill. By this time, I was in outpatient status and home most of the time. One day my parents bought me bunk beds. My Dad and I were setting them up and he said, “Bill, take those braces and that crutch and throw them under the bed. I don't want to ever see them again. You don't need them. You don't want to be a cripple.” So, under the bed they went. Of course, my mother was extremely upset. She said, “No. The doctor said he needs these.” After two days of arguing, my dad won and the braces and the crutch stayed under the bed. I think I only used them a few more times: when I went on long walks and when I returned to the hospital for my inpatient treatments.

I remember growing up through my adolescence years, being known by my friends as “the polio kid.” A lot of the mothers of my good friends wouldn't let their sons play with me because I had polio. There was that persistent fear among mothers in our community of East Lansdowne that their child would come down with polio.

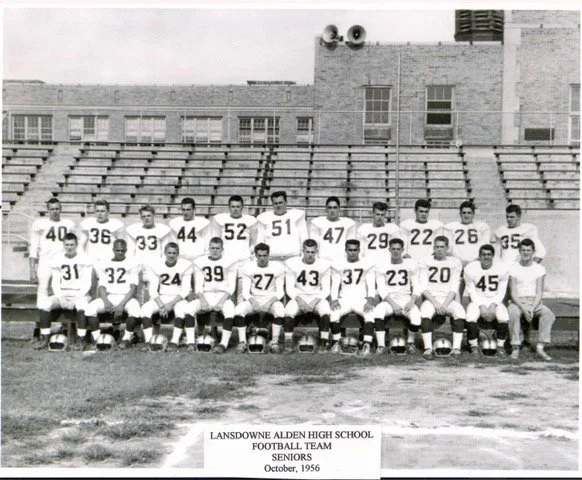

My leg got stronger and stronger, and I persisted on doing things that perhaps I shouldn't have done without the brace. My father was a tough, German born American and he felt that I didn't need the brace or crutch. In time, I was able to get on my own two feet, walk and eventually run (even though I'd stumble and fall often). But I always got up and moved on - trying to keep up with my friends. My father pushed me hard to get stronger and to rid myself of that brace and crutch. He did not want his son to be a cripple. I was able to make the high school football team, although I can't say I played a lot. Later, I played on the lacrosse team and was accepted into the Army ROTC program while a student at Gettysburg College.

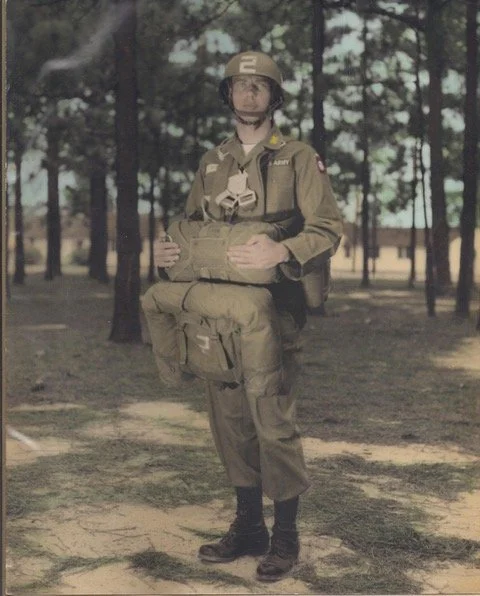

When I applied for ROTC, one of the disqualifiers was infantile paralysis. I filled out the questionnaire honestly. As a result, the Army had to get a neurosurgeon from the Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, DC. to come to the college and give me a thorough neurological and orthopedic exam. The day was long and arduous consisting mostly of strength and agility tests to my spinal column and legs. He reluctantly passed me and I was admitted into the program. I graduated from Gettysburg College and was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the United States Army on the same day. I had a two-year obligation. I upset my mother tremendously when I volunteered for airborne (parachute) duty in the 82nd Airborne Division followed by ranger training. Pushing myself mentally and physically through life’s challenges, even with a weak leg and drop foot was my personal mantra allowing me to stay focused and motivated to overcome the effects of polio. I constantly tested my polio leg to see if I could reach the next bar.

I've always had a limp, which I hid as best I could. Getting into the airborne and meeting the rigors of being an airborne trooper was very challenging and a real test for my polio leg. I had a lot of PT - running, calisthenics, long forced marches that really helped reinnervate the anterior horn cells and muscles in my leg that had been destroyed by the polio virus. I also attended the Army’s Ranger School, and I was very lucky to complete the training and graduate. Ranger training was the most difficult thing I ever did. My polio leg gave out on our last patrol and I went down hard. I will never forget the fellow ranger (a West Point graduate) who picked me up and carried me across the finish line. Had that not happened, I would not have earned my ranger tab.

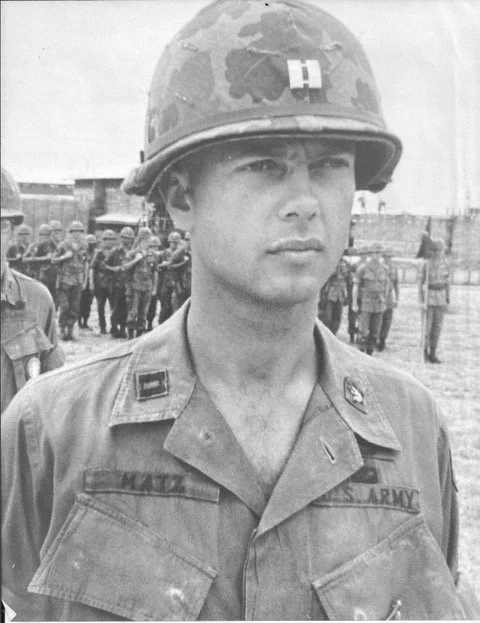

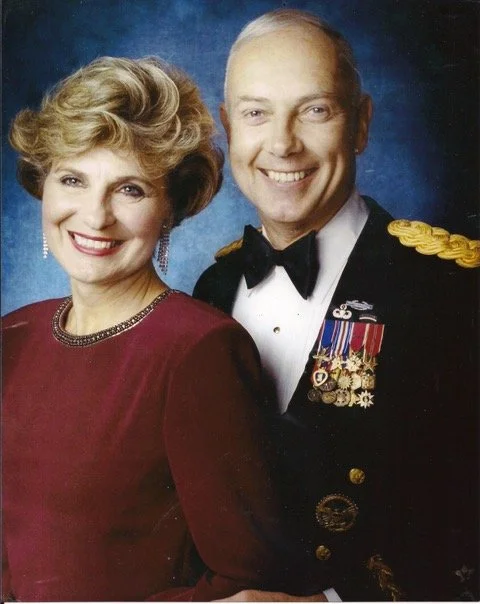

While on leave from the 82d Airborne Division, I met my wife, Linda who was vacationing in Ocean City, NJ, with her sorority sisters from Drexel University. Three years later, in 1966, we got married. Several months later, I left for Vietnam leaving my young wife and our six month old son, who stayed with my wife’s parents in Hamilton, NJ while I was gone. The Vietnam War was heating up and many of my fellow officers were answering the call. Twelve months of combat in the Delta rice paddies and mud fighting against a determined enemy would be a major test for me, and a defining moment in my toughest battle - my struggle with polio!

Even with a size 12 on my left foot, size nine on my right foot and a much thinner/atrophied right leg, I ended up spending 33 years in the infantry. I served in Vietnam, and was wounded on the first day of the Tet Offensive while commanding a rifle company in the Mekong Delta. My military doctors improvised a Jones Bar (a comprehensive ankle-foot orthosis for drop foot and other polio related foot/lower leg deformities that was often prescribed in the 1940’s-’50’s) for me while I was serving in Vietnam. This, coupled with an ankle-calf brace that I wore inside my boot, helped me get through my arduous military career. In 1995, I was diagnosed with Post Polio Syndrome (PPS) and today I continue treatment for my PPS at the Washington DC National Rehabilitation Hospital’s PPS clinic.

I retired from the Army as a Major General in 1995 after numerous parachute jumps and overseas deployments and a long, memorable career with soldiers. After retiring from the military, I served on the Veterans Disability Benefits Commission and as President of the National Association for Uniformed Services, fighting for benefits for veterans and their families. In 2018, President Trump appointed me to serve as Secretary of the American Battle Monuments Commission where I served until 2021.

It was an extraordinary opportunity to be with the President and First Lady, rendering honors at the 75th Anniversary of D-Day ceremony at the American Cemetery in Normandy, France, 2019. One hundred and seventy-one World War II veterans attended.

After I retired from the military and the first Trump Administration, I knew I wanted to write about my life as a polio survivor. Many friends and my post-polio doctor strongly encouraged me to do so. “Bill, yours is a unique story among today’s many polio survivors and should be told,” they would say. It took three years researching and writing, but publishing My Toughest Battle: A Soldier's Lifelong Struggle with Polio has been a cathartic as well as a pleasant experience for me. I was able to include details of those 30+ years in the military that I had never spoken about before.

I don’t know how other survivors feel, but I was always embarrassed, almost ashamed, that I had polio. I always did whatever I could to hide its effects. When I was in the locker room after football practice changing, I always draped a towel down over my weaker, atrophied leg so even my closest friends, my teammates, couldn't see it. I never talked about my polio. Obviously, my family knew it and the young neighborhood kids when I was first released from the hospital knew about it. But it has been interesting to see the reactions of many of my friends after they read my book. My high school, college friends and fraternity brothers, as well as many of my colleagues in the Army said, “Bill, I never knew you had polio. I never knew that.” Yes, there was a certain shame that I carried with me through my adolescent years and even into early manhood. Whether that was good or bad, I don't know. I do know I just wanted to be a normal boy and be able to do what all my friends were doing . . . and I didn’t want to be remembered or labeled ever as a “cripple”!

My story has no final ending, but in telling it I have been able to reflect upon what I feel has been a life well-lived. My challenges came early, starting with overcoming polio paralysis which is when I first gathered the fortitude to confront them. Like so many polio survivors, mine is a story of how perseverance, tenacity and faith drove a young boy to overcome a serious crippling disease and fulfill a life of service to our country. I hope my story can inspire others to fight and overcome their challenges.

The subtitle of my book reads: “A Soldier's Lifelong Struggle with Polio.” Without question, fighting the debilitating effects of polio wasn't easy. But then again, as all polio survivors know, life isn't easy. We have all taken that first step, then another, and another. We are a strong, courageous lot! For many of us, the never-ending battle with polio continues with the worsening effects of post-polio syndrome complications. It will never be over.

For me, conserving energy is paramount in my treatment today. At age 86, wearing an ankle-foot orthosis, Jones Bar, and using a cane for support, I continue to ”soldier on.” We polio survivors are of stout heart and mind and will never let the burdening effects of polio or other setbacks stop us!

Major General William M. Matz, Jr US Army, (Retired)

Notes:

I am grateful to Carol Ferguson for her editing and constructive suggestions in writing this article.

Thank you Casemate Publishing for permission to use these photos.